It started as pins and needles in my feet and, actually, it wasn’t unpleasant given that a) it wasn’t totally unexpected and b) it was the result of a steroid injection to my lower back to mitigate pain and inflammation. I guessed that meant it was working.

The sparkly sensation rapidly climbed up my legs, a friendly army of ants, and it was more fascinating than alarming. But when it came time to stand, my numbed legs simply collapsed beneath me. Fortunately, a doctor and nurse caught me before I hit the floor.

“I guess we’ll put her in a chair,” one suggested as they gently helped back onto the table. Well, that was weird, I thought — not only the inability to stand on my perfectly intact two legs but also to be referenced in the third person as if I wasn’t there.

“Guess I should have told you how chemically sensitive I am,” I told the doctor with whom I shared a giggle.

But not being able to use one’s legs isn’t funny, of course. I have several friends with disabilities most of whom I met volunteering with Eagle Mount Bozeman — a nonprofit providing recreational opportunities for people with disabilities. My friends just accept and deal with it. After all, what choice do they have?

For nearly three hours I was unable to move a toe let alone lift my foot off the floor without using my arms to pull my leg up and, even then, it was difficult. I’ve seen my paraplegic friends do this countless times getting into their wheelchairs, handcycles or a monoski. So, it was a fascinating experience to have the same condition. Of course, I had the privilege of being fairly certain it was only temporary.

Because I had several hours with not much to do, I pondered what life would be like without the use of my legs. I think about ableism a lot but not in terms of myself necessarily (although I am starting to speak up about my own problems with audio processing and how people can provide appropriate accommodations for me).

Everywhere I go I see evidence of ableism — discrimination against those with disabilities. Buildings without wheelchair access are the most obvious. I had one friend sue the local state university over a lack of access. He lost the lawsuit on technicalities but it likely prompted the installation of an elevator in Montana Hall which was constructed in 1898 and where the president’s office is located.

When I asked my friend Liz Ann Kudrna about her experience with ableism she spoke of having to hound a building manager for an automatic button to open the door to the building where she runs a Pilates studio. And not just for herself but for her clients and those of other businesses in the building. He’s put her off for more than a year and she’s still waiting. Liz Ann is aware that because the building predates the Americans with Disabilities Act, the landlord is not legally required to make the modification. But that shouldn’t matter, she contends.

“Ableism doesn’t fall into what is legal and what isn’t,” she says. “It falls under what is humane.”

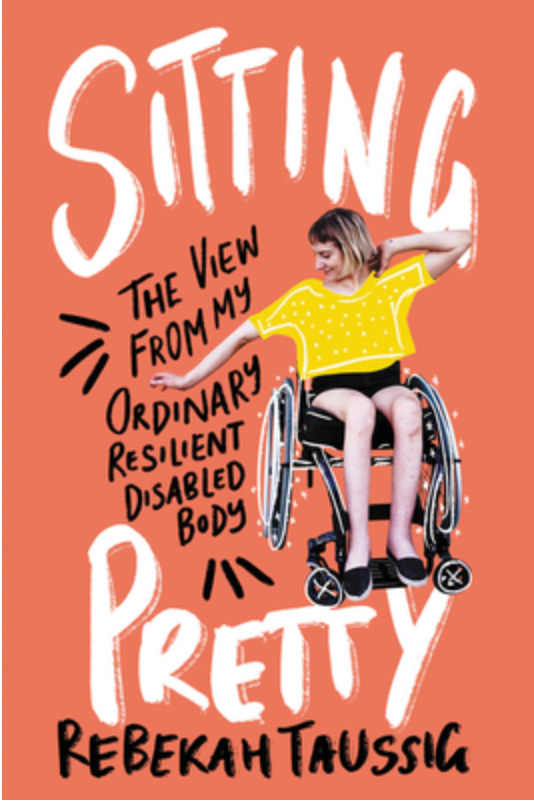

My definition of ableism is surely too simplistic as is that of the Oxford English Dictionary, according to Rebekah Taussig. In her book “Sitting Pretty: The View from My Ordinary Resilient Disabled Body,” Taussig quotes the OED’s definition of ableism: Discrimination in favor of able-bodied people.1

“The Oxford English Dictionary also leaves little room for one vital piece of the story: disability is shaped just as much, if not more, by context than by the body,” she writes.2

She uses an example to illustrate her point: Before glasses existed, many people who function within society today, might have been considered blind. I might be among them; my mother, who’s worn glasses since she was eight, most certainly.

Taussig’s definition is more nuanced and speaks of disability within the context of society rather than the body: “Ableism is the process of favoring, fetishizing, and building a world around a mostly imagined, idealized body while discriminating against those whose bodies are perceived to move, see, hear, process, operate, look, or need differently from that vision. In other words,” she continues, “ableism is one possible answer for a young girl seeing herself as valuable as a princess one week and deflating into shame and self-loathing the next.”3

So, I ask you, is this the world you want to live in? I know I don’t.

I’d love to hear about your experiences with ableism. Please post them in the comments and let’s chat.

Oh, and in case you were wondering, I’m walking fine now. And my back? It’s better but not perfect. Thanks for asking.

Taussig, Rebekah, Sitting Pretty: The View From My Ordinary Resilient Disabled Body (New York: HarperOne, 2020), 8.

Taussig, Sitting Pretty, 9.

Taussig, Sitting Pretty, 10.